“In the Kingdom of Kitch, you would be a monster!” So goes the famous line in Milan Kundera’s 1984 novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Felivered to the protagonist Tomas by his lover Sabina. In the story, Sabina embodies the human search for complete “lightness of being”, and identifies kitsch as something that needs to be shed, like constructive skin, for representing the suffocating ugliness of familiarity she feels pinning in her back. But there’s a charm in familiarity also, isn’t it there? and surely, wrapped up in kitsch is sentimentality too, and the emotional weigh put on objects and knowable images.

It is easy to drift off and think of that kingwom, of what shape it would take and what sort of monster would inhabit it, when standing before the works of Charline Von Heyl and studying their forms. How might a painter like Von Heyl -Who has such a masterful knack for allowing the broadest range of us to pick out recognisable elements in her abstract works- visualise it?

In an interview with Even Magazine some years ago, von Heyl addressed the very subject of kitsch, saying: “There’s an immense satisfaction that I get out of a perfectly curlicued line, for example, or a Disney face. Kitsch is not ironic the way I use it. Kitsch, for me, means a raw emotion that is accessible to everybody, not just somebody who knows about art.

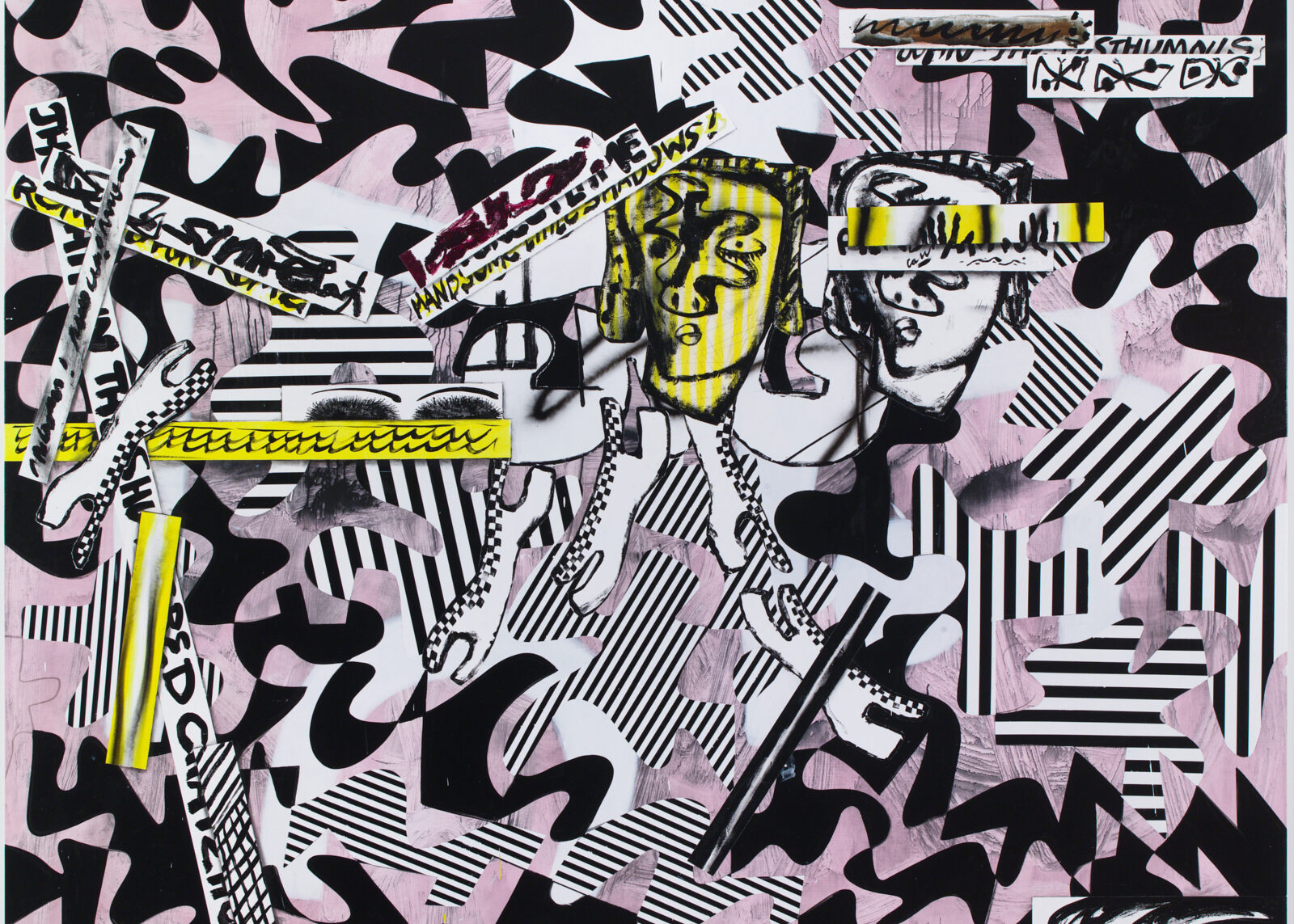

That’s where kitsch comes from to begin with: it was basically art for the people.” We could say, in some ways, that von Heyl is a sort of quasi-anthropologist, who mines the world around her for aesthetically alluring objects and images to feed into her work. In faces and raindrops, bottles and telephones, leaves and stars, von Heyl’s unashamedly decorative symbols and signifiers pry open her paintings and make them porous to us as viewers.

As a result, we are able to find ourselves in them; as if we could pour our own experiences and understandings into the cracks of them and watch them set. These are paintings von Heyl leaves intentionally without narrative, but they are filled to bursting with elements that make us feel almost as if a story might be lurking there, somewhere beneath the surface.

In the same interview mentioned earlier, von Heyl described the images she creates as “an accumulation of everything that charges me or that invites desire.” And that charge is found looping and riveting throughout all of her works, binding them together, and creating small waves of conversation between them as they hang opposite one another on gallery walls or in her studios. Though each of her paintings feels so distinctly itself, there are marked stylistic recurrences in her work that relate them all to one another.

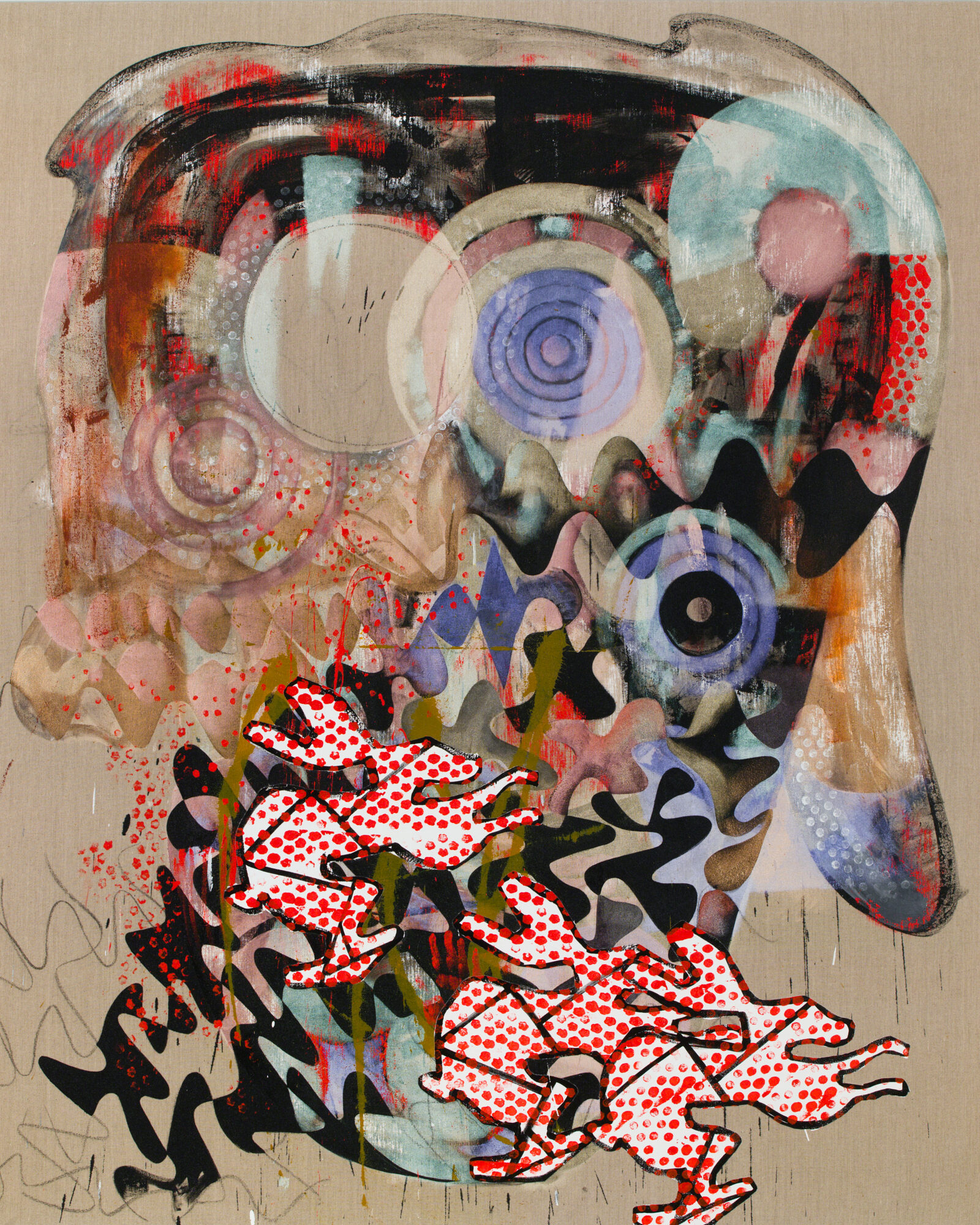

The same curvatures and lines are used, the same arrows are painted with absolute precision, the same female face appears in profile, sometimes only as a phantom trace, and from time to time, the same thick black droplets – which could be raindrops or tears – are scattered across the canvas. Geometric blocks of colour – often in “dirty pastels” as von Heyl likes to call them – rub up against swirling, gestural washes of paint in which the brushstrokes remain visible. In one particular piece, entitled Gacela, 2016, a formidable, cube-like form appears to bob on a wave of rose-coloured leaf forms, rising like a dense black iceberg out of pale, pink waters.

Elsewhere, paintings are entirely monochrome, as in 5 Signs of Disturbance, 2018, where the aforementioned black droplets hang over decorative swirls and expressive acrylic line drawings. Preferring not to sketch out or pre-plan the works she paints before beginning them, von Heyl instead opts to give herself over to a series of aesthetic decisions and happenings beyond her control as the process unfolds. She doubles back on herself, draws faces or figures and then makes them disappear, and follows the lines that flow from her hand in real time. What she chooses to erase, what she does and doesn’t do, the spaces between her gestures, are all as important as what remains on the canvas in the end. And those lines of hers are graphic in their very essence, calm and confident and entirely without wooziness.

Von Heyl once described her process of working in series’ as a sort of “winding up”, as though she has to paint herself into a frenzy of densely-worked pieces in order to wrestle with an idea until she manages to tease it out in paint, at which point she can then unwind and allow for freer, or looser, works to be made. That spiral image is important. Perhaps each of her paintings could be seen as curved forms that slot into the bigger spiral, helix or curlicue of her practice, twisting ever-closer towards the centre of something. For all that movement, though, her paintings are still remarkably still, and even more remarkably silent, meditative, and quietly emotional spaces. Movement might also naturally appear to conjure depth too, but alongside this silence von Heyl wants to retain the two-dimensionality of her surfaces too. She has even been known to sand the surface of her paintings in order to achieve the appearance of absolute flatness she desires.

These days, von Heyl splits her time between New York, and the studio she has on the outskirts of Marfa – the small but legendary arts commune town nestled in the high desert of West Texas. After being awarded a residency at the prestigious Chinati Foundation in the town in 2008, von Heyl fell in love with the place and has returned for several months every year since. In this scorched stretch of desert landscape – where Donald Judd famously found a new creative energy and bought two ranches at which to make his minimalist masterpieces for the rest of his life – von Heyl is able to find a certain clarity of mind and detachment needed to experiment. It’s a place to find the silent, abstract spaces she searches for; a place in which new paintings can come into being, away from the noise.