In the early 1990s, a wave of emerging artists were returning to figurative art melding abstraction, minimalism, pop, mass media, and at the time, the new media — the internet.It was at this pivotal moment in image-making that the British artist, Nicola Tyson would have her first solo exhibition at an artist-run space in lower Manhattan called Trial Balloon.

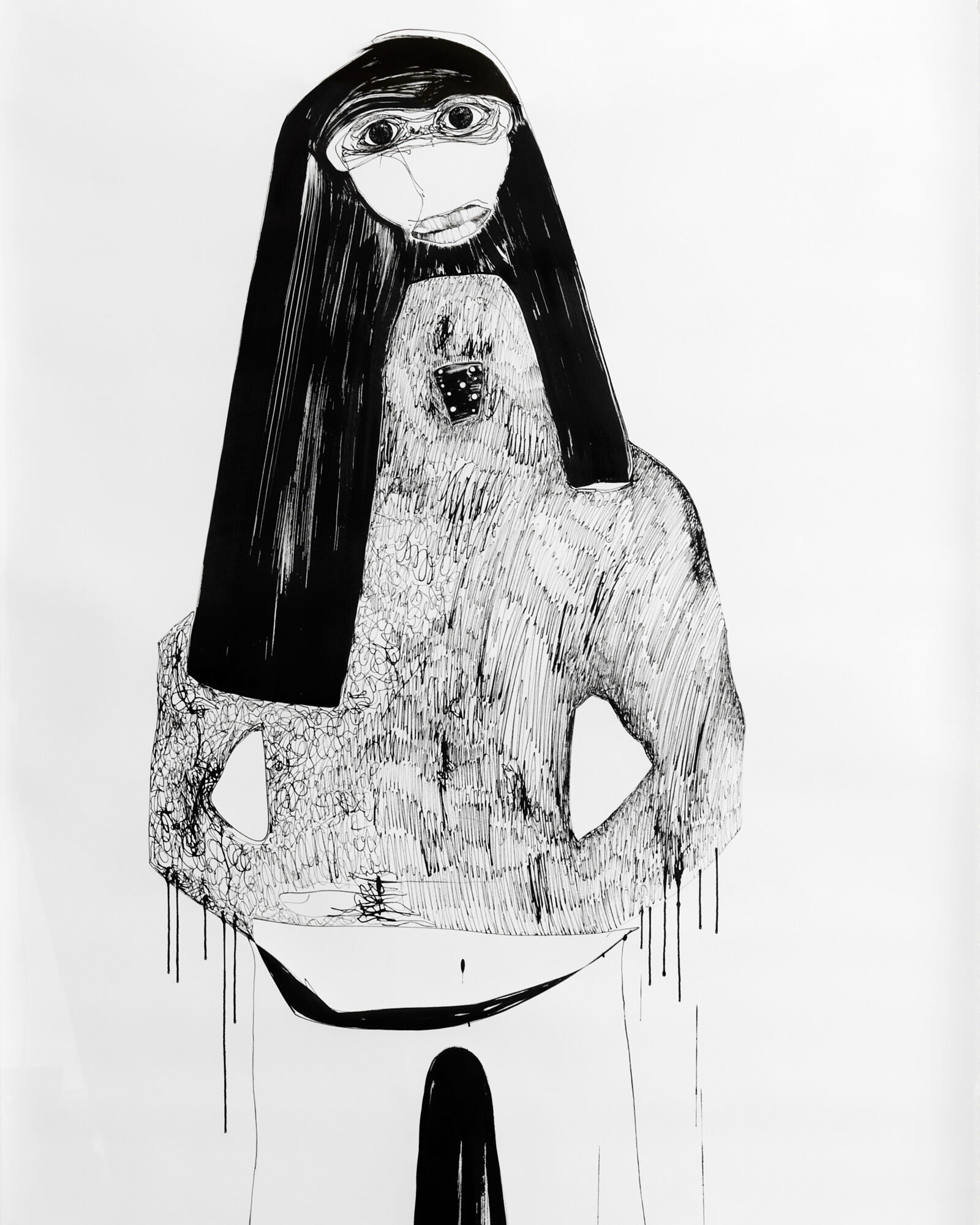

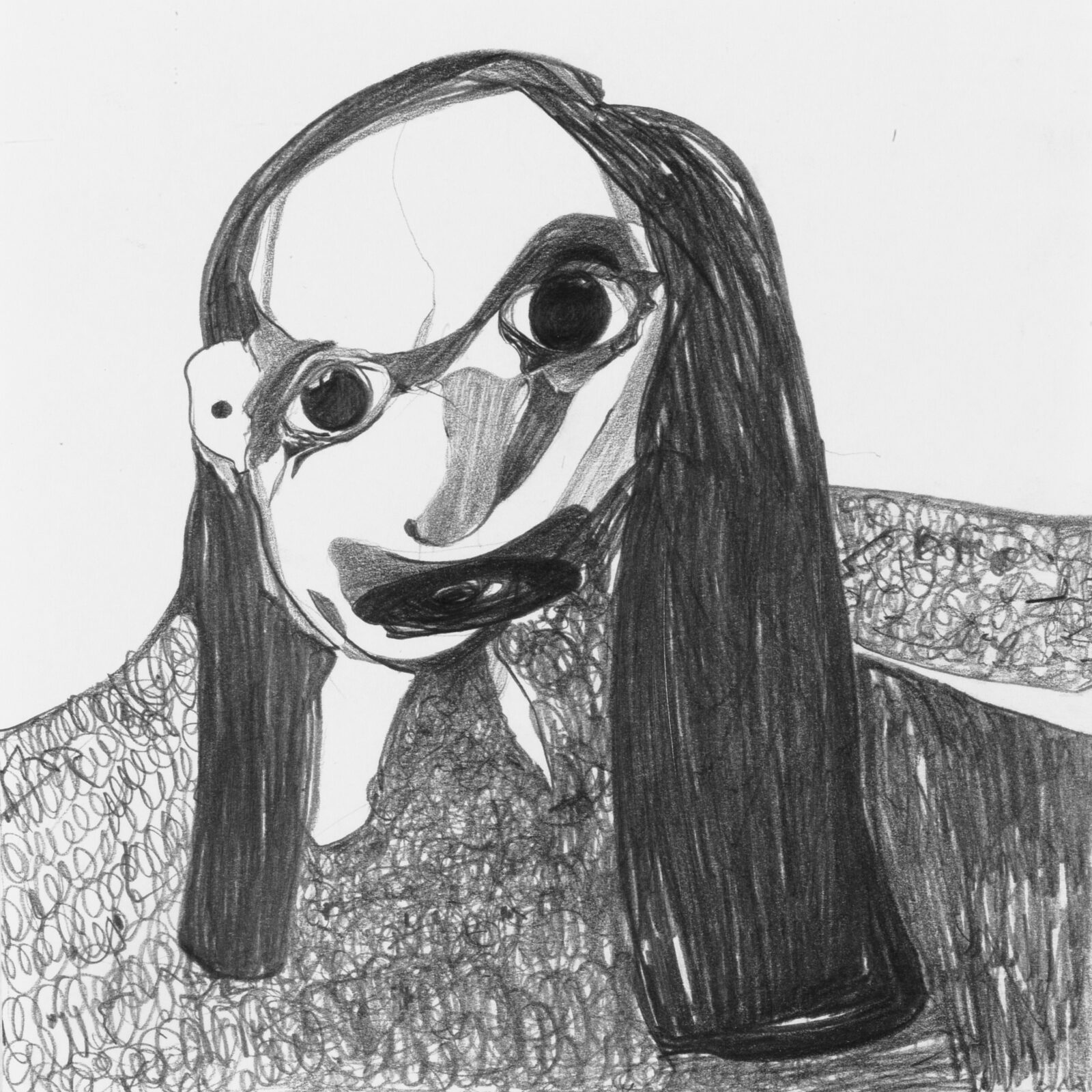

Tyson showed a group of five paintings all focused on the body and its various parts — dismembered and reassembled — like a cast of characters zapped from a virtual reality — what the art critic Jerry Saltz described as “sexy, dreamy, a little scary and a little unresolved,” in his 1994 review of the show.Further exploring this strange iconography, Tyson drew, not from memory, but spontaneously in real time, working directly onto the canvas, unencumbered by her classical training in life drawing and energized by the risk in returning to the figure, a subject that was considered taboo in late 20th century art circles.

Throughout the 90s, she carried on developing her unique figurative expression using a limited palette of oil paint on canvas. In 1995 she showed a new group of paintings at the legendary Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London. The paintings were made up of solid body forms, some in pairs and others solitary, but all appeared to be in motion on a flat monochromatic background. The Swimmer, 1995, now in the permanent collection of the Tate Gallery, is one such painting. It’s composed of few colors; blues, pinks and black. The figure is positioned vertically with a bulbous head and soft velvety winglike arms outstretched horizontally. From what appears to be an aerial perspective, it floats upside down on a pale blue background. It’s both seductive and unsettling, minimalist and arresting. The ‘stop-action’ state of the figure allows the viewer to consider the form that’s neither male nor female, alien or animal but simply an existential being, centered, although slightly adrift.

By the turn of the 21st century, the burgeoning technological revolution of the 90s had exploded. The internet became the mainstay of communication. Now, social media platforms proliferate and picture-sharing apps are ubiquitous.

Undeterred by all the ‘noise,’ Tyson continues to expand on the subject of the figure simply by using line and color. She switched from oil to acrylic paint “mainly because I became too sensitised to oil paint.” The odorless property of acrylic was curative and its fast-drying property fuelled a new sense of urgency that she put into her image-making.

Keeping to a limited palette and using a dry-brush technique, she collages color, strategically revealing the underpainting in areas on the canvas. She builds up the surface this way while at the same time making marks, quick outlines of the figure in acrylic, that characteristically lend the subject a more agitated, more frenetic nature. The distortion of proportion and perspective further adds a psychological reading of the subject, what she once described as “psycho-figuration.”

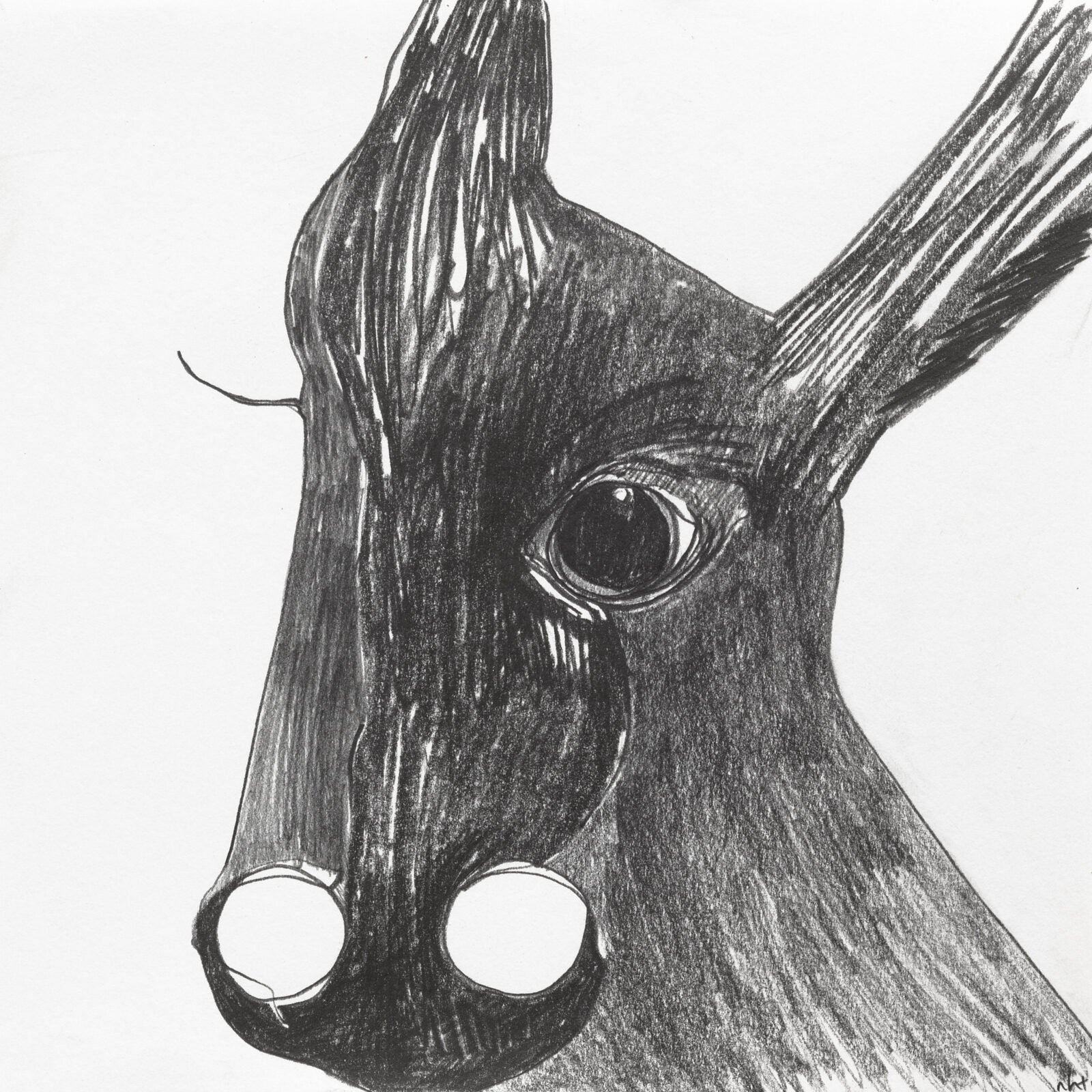

Tyson currently lives on a farm in Upstate New York. She invited me to visit her studio, a nondescript space later added to the 19th century rustic farmhouse that she inhabits. It has low-ceilings and windows that open onto an expansive landscape. With natural light pouring in she works on different paintings simultaneously moving from self-portraits to figures in daily acts drawn from country life as much as from her routine visits to New York City. Her imaginative cast of characters are in various stages of development. They are made more primal by her uncalculating approach to image-making in relation to universal issues of identity, gender, sexuality and representation in 21st century art.

DO YOU SEE YOURSELF AS PART OF A GROUP OR MOVEMENT, OR DO YOU FEEL YOUR WORK EXISTS IN SOME DEGREE OF ISOLATION?

NT Originally my work was rather singular and I felt quite happily alone in that. I began painting in the early 90s, when painting was considered a bit redundant (yet again) and neoconservative by some members of the conceptual art world. Hard to imagine now! I’d chosen to go back to painting after working conceptually for a few years when I looked to feminist theory as a source of inspiration and guide. After some time, however, I started to become increasingly frustrated. These ‘rules’ began to structure my imagination. What I really wanted to do was work completely intuitively. I felt that if I took a subjective approach to figurative painting — what I dubbed back then as ‘psycho-figuration’— I could start to invent some new and useful ‘information.’ At the time, such an approach to figuration was still fairly uncharted territory, at least for a woman artist. Now there is no shortage of bizarre figuration out there and that’s just great because it serves to challenge me to delve deeper and discover what it is I can add to the argument for figurative painting.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE STATE OF CONTEMPORARY ART TODAY?

NT It’s very dispiriting how market driven it is and too fast and too big. I remember life before art fairs — it was very civilized. Soho in the 90s was still very much an art community.

The global thing is too much to wrap one’s head around — an oppressive and vertiginous pressure. There’s no ‘local’ art anymore, just this global generic spectacle and the artist-as-entrepreneur thing which is kind of horrifying especially if you’re not that type of an artist — like me!

YOU GREW UP OUTSIDE OF LONDON SURROUNDED BY NATURE WHERE YOU HAD YOUR EARLIEST ARTISTIC IMPULSES. IS IT ESSENTIAL FOR YOU TO BE IN A NATURAL ENVIRONMENT TO MAKE WORK.

NT Well I didn’t grow up in the countryside, but in a boring postwar suburb in what had once been farmland west of London. However, we had an unusually big garden because we were adjacent to a point where the British Rail line passed under the Piccadilly tube line, (via a long tunnel), so the two railway embankments combined meant we had many extra acres to explore — by trespassing of course!

I was very interested in what they called ‘natural history’ then and in 1970s environmentalism. I thought I would have a career in that field, but come adolescence my priorities changed and I became more interested in culture rather than nature — particularly pop culture. But those early interests still surface in my work. As a child, I used to draw — document — a lot of plants, insects and birds. I can still immediately spot a caterpillar when out walking, as my eye is trained on those details rather than what my companion is wearing!

But no, I really don’t need to be in nature to work. In fact, I ended up living in the Hudson Valley rather by accident when the rent on my Soho loft went up astronomically. I thought it would be a temporary situation, but then I just stayed. I’m more of a city person at heart in truth — I thrive in the hive — so I shoot down to the city every few days. But I also love being in nature, so I guess I reap the best of both worlds!

YOU CAME TO NEW YORK ALMOST 30 YEARS AGO AND STAYED. HOW HAS THIS INFLUENCED YOU? DO YOU IMAGINE YOUR WORK WOULD BE DIFFERENT HAD YOU STAYED IN EUROPE?

NT I left the UK after graduating from Central St Martins in 1989. It was just as the students at Goldsmiths were organizing into what would become the YBA scene of the 1990s. My only regret was missing out on a lot of partying and all the fun that was going on at the time in the London art scene!

New York was of course already an international art center, although still a bit flat on it’s back after the real estate market crash of the late 1980s. When I arrived, it was rather serious-minded with political art the hot topic. I had been attracted by aspects of this — to be where so much great, cutting-edge work was being made, especially by women artists that I had studied at art school.

So partying aside, I do feel my work benefited from living here. Perhaps had I stayed in London, I think I might have been seduced into making conceptual one-liners — taking a quicker, slicker, more superficial approach — and I might not have dug in deeper and taken the risks that I did in order to find my true voice, as it were.

IS THERE AN ARTIST COMMUNITY IN THE HUDSON VALLEY? DO YOU SEE MANY POSITIVE/NEGATIVE CHANGES TO THE REGION YOU’VE CHOSEN TO LIVE IN?

NT Here in New Paltz in the mid-Hudson Valley, I’m equidistant between the established art world of New York City and the burgeoning art scene an hour and a half in the opposite direction, north of here, around Hudson. There’s also an emerging scene not so far away in Kingston. But I generally head south to the city to get a dose of the art community I’ve thrived in for so many years now. Like I say — I do need a regular dose of the big city.

The Hudson Valley is under quite a lot of developmental pressure these days, but we are very lucky in New Paltz, in that much of the surrounding landscape is now protected in perpetuity by various organizations, such as the Nature Conservancy, the Open Space Institute, and local entities like the Mohonk Preserve.

ARE YOU WORKING TOWARDS A NEW SHOW? DO YOU INTEND TO EXHIBIT NEW WORK IN 2020

NT Yes. In September 2020, I’ll be showing new work at the Friedrich Petzel Gallery’s uptown space on East 67th Street that’s currently under renovation. I’m excited to show in an elegant, prewar Upper Eastside apartment space. These gigantic Chelsea spaces have always been kind of hard for painters like me. I’m a slow worker and I only have a relatively small studio at the back of my old farmhouse. I still miss the late 19th-century industrial spaces that made Soho so special. I love that the art world is recolonizing more intimate spaces again.